Inside this post: A deep dive into executive functioning in teens. This article is the first in a series.We encourage parents to also read: 10 Simple Ways Parents Can Help Their Teens with Executive Function Skills

Parenting teens can be lonely, especially when our kids struggle with things we see others handling well. The urge to compare is strong, as is the urge to protect their privacy. This often leads parents to head to the “virtual watercooler” of social media groups where we can ask questions and present issues, sometimes anonymously.

In many of these conversations, the term “executive function skills” emerges, including why many people are struggling with these capabilities or why executive dysfunction is on the rise.

There are more than a dozen executive function support groups on Facebook, many of which cater to parents seeking ways to help their children or teens. But what are executive function skills? Why haven’t we heard of them before? Are they something new? Why are so many teens struggling with them?

What are executive function skills?

The term may sound new, but executive function skills are things we’ve always done. And while these are all learned skills, they aren’t specifically part of any curriculum.

Instead, they are things most of us figure out over time. And while some are explicitly taught (such as how to organize writing or plan out a research paper), they aren’t presented as significant life skills.

According to Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child, “Executive function and self-regulation skills are the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully.”

Child Mind Institute describes executive functions as “mental skills that we use daily to get things done. We use them to set goals, plan how we’re going to do something, prioritize, remember things, manage our time and possessions, and finish what we start.”

How do we use executive functioning skills?

Researchers agree that these skills depend on three interrelated brain functions:

- Working memory, which allows us to retain information over the short term,

- Mental flexibility, which allows us to maintain or shift focus as appropriate, and

- Self-control, which enables us to prioritize and resist impulsivity

These brain functions are responsible for a host of interrelated skills that are considered essential for success in today’s world, such as:

Response inhibition: This allows us to resist knee-jerk reactions by evaluating a situation and considering the implications before acting. This is an area where some parents actually note regression in the teen years, due to the dramatic changes in the teen brain. Impulsivity is almost a hallmark of the teen years – before judging your teen too harshly, look back at your own lives – don’t you have moments you wonder “What was I thinking?”

Emotional control: Like response inhibition, this is highly influenced by changes in the teen brain, particularly in the amygdala. Many parents are caught off guard by the emotional rollercoaster they experience during the teen years. Mild-mannered middle schoolers become teens who rage at minor slights or collapse sobbing at perceived injustices. The raging hormones of the teen years suppresses rational thought, making teens more emotion-driven than young children or adults.

Working memory: This is the ability to simultaneously remember and recall information, even while doing another task (i.e., remembering steps in a series while engaged in those steps). It blends the past and the present and allows us to make connections and understand cause and effect. Deficits in other executive function skills impact working memory. For example, struggles with sustained attention or emotional control can hinder teens’ ability to remember even the simplest sequence (such as put dishes in the sink, add detergent and turn it on) or where they left their math book. Strong working memory can lead to more sustained attention and when teens have the information they need at hand, they are likely to exhibit better impulse control and more flexible thinking. Kids with working memory deficits may be labeled lazy. They may be behind in math and reading skills and struggle to take good notes

Flexible thinking: The ability to adjust to change is an important skill not only in work and school environments, where one needs to transition from one task to another or pivot when priorities change or obstacles arise but also for personal relationships. Flexible thinking allows one to see alternate perspectives, to admit to being wrong, and to be able to take advantage of new, unexpected opportunities. As teens move into adulthood, they don’t know what they don’t know; being open to new things can also lead to interesting life experiences or possibly career opportunities.

Sustained attention: The ability to pay attention to a task even when feeling fatigued, bored or in the face of external distractions is essential. But teens sometimes “space out.” They may forget their gym bag next to the door or get out of the car without their lunch. They may complete their homework and leave it on the desk at home. Inadequate sleep, distractions (such as a text or being called to dinner) or even hormones can contribute to these lapses.

Task initiation: For many, finishing a task isn’t the issue; it’s getting started. Procrastination is a common issue among teens and young adults; studies show that chronic procrastination may be linked to anxiety and depression.

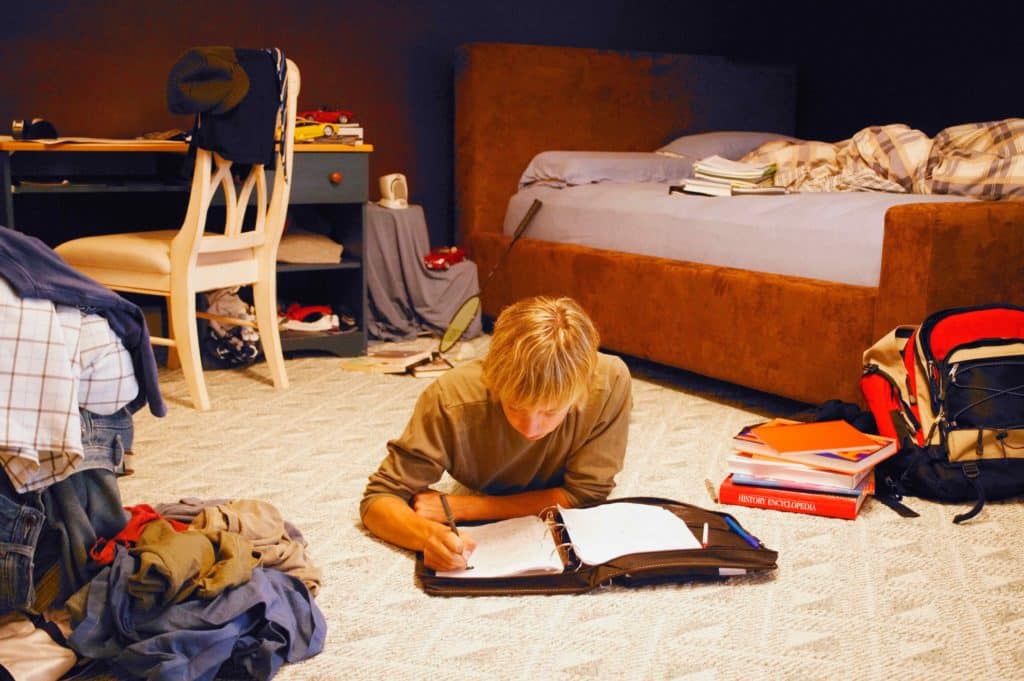

Organization: An entire industry relies on struggles with this skill. This involves not only establishing organizational systems, but also maintaining them. This is important when it comes to both physical space (i.e., teen’s messy bedrooms) and ideas. This is one skill you probably have spent some time teaching, and one you might struggle with yourself. Parents and teachers alike provide a variety of tips and tools to foster organization and you can find thousands of books on the topic. (Related: 5 Amazing Organizational Apps for Teens)

Time management: This is another skill that is more complex than it appears on the surface. It requires not only estimating how long a task will take but also how much time one has. It also assumes a basic “sense of time” an innate ability to estimate how long say 15 minutes is and what can be accomplished in that time. Lack of time-management skills is a common complaint, which may be why there are so many resources available. But it requires more than planners and sticky notes. Often the issue is time awareness. Teens often lose track of time, or underestimate the amount of time a task till take. (Read more: Time Management Can Be Tricky for Teens: Here’s How to Help)

Prioritization: This is a planning skill that involves determining the steps of a task and deciding which are most important. It is also discerning what is not important. Particularly with long-term projects Teens may be caught off guard by not planning ahead for contingencies and they run out of time. Here we see the confluence of several other executive function skills such as flexible thinking, when external changes or disruptions, faulty time management, inability to sustain attention, or poor organization results in having to choose what goes in and what gets dropped.

Goal-directed persistence: This incorporates most of the other executive function skills and is one of the last to develop. It is the ability to maintain focus on a long-term goal and follow through on achieving it, despite distractions and competing needs. (Read more: How To Help Your Teen With Setting High School Goals) Teens are bombarded with information that doesn’t necessarily happen on a regular schedule: homework, extra-curricular schedules, try-outs, etc. When you add in the demands of relationships (family, friends, romantic interests), it’s no surprise many of them report feeling overwhelmed.

Metacognition: The last skill to develop, it changes how the brain works. This is knowing you have thoughts and can use them to make sense of the world. It allows you to step back and evaluate what you have done and to assess your strengths and weaknesses. Progress in this skill is seen when teens recognize they are struggling and ask for help or develop metacognitive strategies on their own. For example, they may use a self-cue (like putting a sticky note on the door to remember to bring gym clothes). However, this strategy only works if you actually remember to use it.

Why are executive functioning skills important in the teen years (and why do teens struggle with them?)

Executive function skill deficits are often observed for the first time during the early teen years. Sometimes these struggles are indicative of an undiagnosed learning disability (such as ADD or Autism), but many times they are simply a sign of an undeveloped frontal lobe in a teenage brain, which is perfectly normal.

Dr. Peg Dawson, psychologist and author of numerous books on executive skills, including Smart but Scattered and Smart but Scattered Teens, says that it’s normal to struggle a bit with these skills, particularly during the teen years. Mastering these skills is a process, and it’s developmentally appropriate for teens to have ups and downs as they figure things out.

Her message to parents:

“Stop worrying. Don’t expect them to be proficient when they graduate high school or even when they graduate college.” She says executive skills take a minimum of 25 years to fully develop in typically developing individuals (and even longer in neurodiverse individuals).

Children start learning these skills as toddlers and build on them as they learn more complex concepts and take on more responsibilities. Executive function skills develop over time, often through repetition, until they become second nature. Like other skills, they are only maximized through practice.

While full mastery isn’t reached until the mid-20s, teens should have at least a basic understanding of these skills and why they are important, or they are going to struggle when they get to college or start their first jobs. These struggles can cause self-esteem issues as well as anxiety and depression, which will further inhibit skill development – an unpleasant and potentially dangerous loop that can be difficult to break.

The past couple of decades have seen tremendous advances in neuroscience, but true understanding of the brain’s functions is relatively new. The use of functional magnetic resonance imaging technology (fMRI) proved to be instrumental in discovering how the brain works (unlike early research methods that depended on viewing brain slices through a microscope, studies could now safely be done on active brains).

This is how, for example, neuroscientists learned that different areas of the brain control different functions and that not only do some of these areas develop slower than others, but the connections between these sections also continue to change and grow, often at an uneven pace.

Executive function (EF) skills are just one example of this uneven skill development. While some EF skills build upon each other, different skills reach full maturity at different ages, and sometimes not until adulthood.

This is particularly true of the mental processes related to decision-making, reasoning and problem-solving. Because of key changes in the brain, (physiological changes to the white matter of the brain and the connections between brain regions), teens analyze information and evaluate risk and reward differently than at other developmental stages. This leads them to rely more on the emotional parts of their brains to make decisions, and to act more on impulse than logic.

What do parents of teens need to know about executive functioning skills

Dawson reminds us that the most challenging times are “when students transition from one level to another, for example, middle to high school, high school to college, or even from college to work.”

Developmentally, students of the same grade level are not all at the same stage. Emotions (such as test anxiety) also may have an impact that can look like executive dysfunction (which will subside as the emotional issues are resolved). Ideally, she says those in transition need support from a teacher or other trusted figure to help “ease them into it.”

“Some parents worry too much,” she says. On the other hand, she adds, “Some parents do too much. They try to micromanage. They are nervous about their kids failing or not meeting their potential.”

While it is normal to want your children to succeed, propping them up and solving their problems is not the answer.

Knowing when to get involved and when to step back is a struggle throughout parenthood. We won’t always get it right, but learning what is typical can help reduce clashes and foster a stronger relationship with our teens.

When you are in the thick of raising teens and tweens, we recommend Loving Hard When They’re Hard to Love by Whitney Fleming. In Loving Hard When They’re Hard to Love, blogger Whitney Fleming shares her favorite essays about raising three teenagers in today’s chaotic world. Written from the perspective of a fellow parent, each story will leave you with tears in your eyes and hope in your heart because someone else is saying exactly what’s been going through your mind.

Parenting teens and tweens is hard, but you don’t have to do it alone. Here are some other helpful posts:

Helping my Teens Manage ADHD Was a Learning Experience for Both of Us

Why Teens Lack Motivation And How To Help Your Teen Be More Motivated

Time Management Can Be Tricky for Teens: Here’s How to Help

Ten Important Teen Life Skills They Need To Master In Order To Thrive In Adulthood

Leave a Comment